Intel NUC 9 Extreme Review – Is This TINY Gaming PC Worth It?

Share:

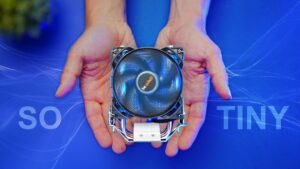

Well guess what showed up last week? The Intel NUC 9 Extreme. I really didn’t expect to have one here right now because after our coverage at CES 2020 it just sort of faded away. Honestly, I really hope that Intel went back to the drawing board since what we saw earlier this year didn’t really inspire much confidence at all. Now the NUC 9 – otherwise known by its codename Ghost Canyon – is really, really expensive. However, it does come in one of these smallest packages I have ever seen for a full-featured PC.

There is a saying that you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, and I think it’s important to approach every review with an open mind, especially since Intel did manage to pack some impressive specs on the NUC 9. In this review I am going to break down this new small form factor system, see how it actually performs, and figure out what exactly it offers for consumers that’s new.

Let’s start this off by explaining what the NUC 9 is. First of all, the NUC 9 series will be broken down into two major categories. So there’s the NUC 9 Extreme, which will come with the Core i9/i7/i5 CPUs and the NUC 9 pro, which will be equipped with Xeon processors that support vPro technology.

Right now the NUC 9 ecosystem consists of two components. The first is called the Compute Element, and in many ways it’s a self-contained PC that’s just missing a power supply and a case. It holds an integrated Intel 9th Gen processor… yes, that’s correct I just said 9th Gen even though the 10th Gen is available right now. It has also has a cooling assembly, a motherboard with all the usual I/O connectors, memory slots, a Wi-Fi 6 module, and space for two M.2 SSDs. You will notice that the Compute Element has a PCIe connector, and that’s meant to interface with a baseboard like the one above. While they will come in different sizes, the daughtercard in our NUC can be used to add expansion cards like a GPU or a secondary PCIe-based storage drive. Others simply act as a power interface and help create ultra-compact systems like the Stack Solo.

The NUC 9 Compute Element will be sold to system integrators to create small form factor PCs or barebones kits like the Razor Tomahawk and the iBUYPOWER Revolt. However, according to Intel, there are already plans to roll out new Compute Elements through 2022, so those could just be bought as drop-in upgrades. That should guarantee that this won’t be a dead-end purchase anytime soon, I hope. The first rollout of the NUC 9 will be via Intel’s Extreme kits like this one. This is a barebones kit that comes with a 5 liter small form factor case, a 500W 80Plus Platinum power supply, and a baseboard that comes with two PCIe expansion slots. You will need to buy your own SODIMM memory, storage, and if you want to game you definitely have to get a dedicated graphics card.

The price for all of this is not cheap, in fact it’s rather expensive. The Core i5-9300H based system is going to run you around $950 USD, the Core i7-9750H is going to be around $1,110 USD, and the Core i9-9980HK which is the 8-core/16-thread based system is going to cost you $1,550 USD. I also need to mention that these are Intel provided prices and it looks like a few of them are already popping up at online retailers. For the time being the Core i9-9980HK model will set you back a little less than $1,700 USD. Before moving on, I do need to mention something very important, if you look at the NUC 9 – specifically the Core i9-9980HK system – and you spec it out with storage, memory, graphics card, monitor, and an operating system, it’s going to cost as much as a gaming laptop or even more than that. If you move into desktop category you can get an insane amount of horsepower for that price. Furthermore, it is a questionable choice by Intel to include a 9th Gen CPU because they are already rolling out 10th gen Comet Lake processors on notebooks. Instead of calling this Next Unit of Computing (NUC), they really should have called it Last Gen Unit of Computing because the specs are quite frankly outdated.

I do have to give Intel some major credit since the NUC 9 Extreme looks awesome with its honeycomb metal mesh for increased airflow and a really tiny footprint. It is also really well equipped for professionals, with two USB 3.1 Gen2 ports and a UHS-II card reader up front. There are tons of additional ports at the back from the Compute Element itself, such as two LAN ports, two Thunderbolt ports, and four USB 3.2 Gen2 ports. To get inside you just have to loosen the two screws and then pull out the top panel. I have to say tanks Intel for including captured screws, I wish more cases had these. That top panel has two 80mm exhaust fans that have power provided through a contact plate installed on the front panel. The next step is to slide off the side panel and now you have access to the Compute Element or the PCIe slots.

Getting into the Element only requires the removal of two screws and the entire front piece just lifts off out of the way. In this unit there are two M.2 slots and two SODIMM slots that can handle up to 32GB of memory at DDR4-2666 or it can take a 64GB kit at DDR4-2400. It’s a bit tight, but installing those components is pretty easy. After that it’s just a matter of closing things up and installing a GPU, if you want.

In order to keep the form factor as small as possible Intel is limiting GPU height to two slots and the length to 8 inches. If you really push the power supply cable so you could get away with 8.25 inches, but that’s just really pushing it. Other than a few GeForce RTX 2060’s, there is a PowerColor Radeon RX 5700 and an ASUS RTX 2070 ITX graphics card that should fit okay, but higher end GPUs are pretty much off the table. Installation of the GPU can also be a bit difficult since Intel’s 90-degree power connector only fits on certain cards. If your card has a more traditional layout like the EVGA one above you will need to fish out a standard 8-pin plug from the wiring harness.

Now once you go through all of that, just pop the two side panels and the top back on, and the installation is done. However, if you need access to the third M.2 slot located on the PCB, it’s a bit more complicated. You will need to remove the Wi-Fi antennas, unplug the power and I/O connectors, take off the other side panel, and then remove the Compute Element. Next take off the heat sink, install the SSD, and repeat the process backwards.

One of the first thing that anyone is going to think of when looking at the NUC 9 Extreme kit is airflow. While it might look like the GPU is preventing air from entering the fan, there are a couple of cutouts in the Compute Element shroud for intake. Also there is an open area under the fan for even more air movement and the air guide should help direct cool air from the front of the case instead of the GPU area. However, what does this all mean for temperatures? Let’s check them out.

Starting with gaming, the temperatures over time remained in the mid-70°C range until pretty late in the test where they gradually rose to mid-80°C’s. The odd thing is that this did not have any effect on frequencies. The CPU clock remained pretty constant at 4.2GHz. Temperatures in Adobe Premiere Pro are pretty much the same story, but you will notice some big frequency dips here. If I overlay the frequencies you will see that the CPU goes into a semi-idle state at certain points. Basically, in those areas the GPU and iGPU are taking over video encoding and decoding. AutoDesk Maya showed some super odd behavior that mirrored what I would usually expect from a notebook. Temperatures start really high and then fall off a cliff, and the frequencies pretty much mirror that. For whatever reason it looks like the Core i9-9980HK is throttling itself even though temperatures are pretty low.

The Ghost Canyon isn’t exactly whisper quiet at full load, but it’s quite reasonable, and does better than our DIY Mini-ITX system.

Before I get into performance, I do want to give you a little insight into what I’m comparing the NUC 9 to. The model that I have comes with the Core i9-9980HK, and when you add 16GB of DDR4-3200 memory, a 1TB SSD, and an ASUS RTX 2070 ITX graphics the total comes out to almost $2,400 USD. Spec’ing out the exact same Intel-based Mini-ITX system with desktop components comes to much less, by about $600 USD. You could get away with even cheaper if you decide to go with a different Mini-ITX case and air cooling. However what happens if your budget is $2,400 and you still want something compact? Well that’s where AMD comes in with this monster of an Mini-ITX rig that I’ve just built recently. It costs about the same as the NUC 9 at around $2,400, it is also beautiful, and you are only sacrificing a little bit of space because the NZXT H1 is still pretty compact.

Onto the results for these three systems. Starting out with Cinebench R20 and it’s pretty obvious that this is a notebook CPU that just can’t match what desktop CPUs have to offer. The same goes for Blender, but I do think it’s important to mention that a few NUC 9’s together could make for an awesome rendering farm in this program. Now we get into something that’s a bit closer to my heart, the benefits of Intel’s QuickSync engine really do come in handy in Adobe Premiere Pro, at least in projects that we are rendering on a daily basis. Even a $2,400 AMD Ryzen 3900X based system can’t keep up with the other two Intel systems, but that result is just a one-off though. In DaVinci Resolve the NUC 9 can’t keep up, but every other system is pretty close to one another. Moving on to Autodesk Maya, the Core i9-9980HK just gets its butt kicked again, but remember in this test and Cinebench the CPU throttled itself big time for no reason whatsoever.

Moving on to gaming, the Core i9-9980HK oddly doesn’t look all that bad compared to the Core i9-9900K, but for $2,400 it’s a poor showing. It just doesn’t offer all that much value, especially when compared to that $2,400 AMD Mini-ITX system. The 1% minimums are also a pretty glaring issue in some games like Red Dead Redemption 2.

From a performance-per-watt standpoint, I’m not really convinced here either. Yes, the NUC 9 is efficient when there is a full CPU load, but it also struggles in apps that stress the processor. In gaming, it’s pretty much a wash since it’s power consumption aligns with frame rates.

In the end, here is the question that I keep asking about being NUC 9 Extreme: Would I buy it? The answer to that is a simple No. This product is not targeted towards the enthusiast DIY market. In fact, this is just a notebook without a display, keyboard, trackpad, operating system, and it runs a previous generation CPU. There is tons of potential here, but my main problem with the NUC 9 Extreme really comes down to price. I mean sure it’s super compact and surprisingly easy to work with, but this seems designed and priced in the past, before the small form factor space got so competitive. Nowadays, beginners can go out and buy a pre-built Mini-ITX system that will cost a lot less money than the NUC 9 Extreme. Maybe this thing could be a good fit for businesses who might be looking for a really small efficient rendering machine for editing, maybe a little bit of 3D work, or if you’re running a gaming cafe this could be a really good fit too. However, for any other situation it’s just a hard sell.